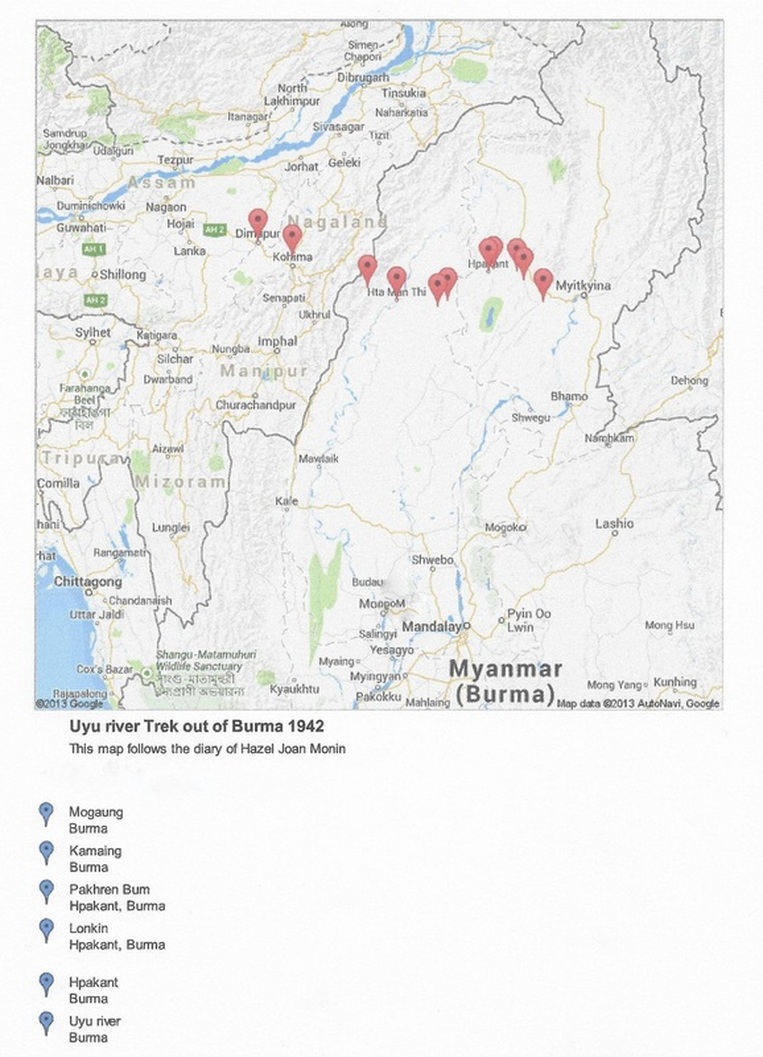

The Trek Out of Burma 1942

Memoirs and Recollections

|

The Burmese Trek WWIIAn Uyu River route, Mogaung to India via Hpakant, Yebawmi, Hta Man Thi

|

|

The Burmese Trek WWII

From Pakan to the next village Namaung the road was winding, slippery and treacherous. We did a good deal of climbing that afternoon, but the climbing was not very strenuous. We came into contact with rain for the first time that afternoon; black thunder clouds caused by the surrounding hills and it was very dark and threatening for some hours. Though walking in the rain was cool and lovely and such a relief from the hot, burning stifling sun - it made the roads more slippery and dangerous than ever. We crossed a very wide river that afternoon by a bamboo bridge, built very low over the water without rails and very frail. One of the bamboos gave away and I went down into the water. We slept that night in the village of Namaung in a Burmese house, which the owners very kindly invited us to share with them. We slept in the front room where their Altar and statue of Buddha resided. We had to sleep with our heads to the altar, as the Burmans directed and instructed us to do. We complied willingly with this regulation of their religion – meaning sheer respect for Buddha. We did about 12 miles that first day out from Lonkin. The next day we left Namaung 11th [May] and completed the journey to Haungpa – a distance of 16 miles or so. We climbed our first very high hill that day about 2000 feet high. On the summit of this hill was a plateau about 3 miles long. This plateau was covered with lovely green grass and huge broken rocks were strewn around carelessly and there were also many dried up stream beds. A very thick mist overhung the plateau and we were unable to see more than a few yards ahead of us. After descending the hill we crossed flat open country – through semi-burnt woods, scorched fields and cultivated ground. We reached Haungpa late that afternoon. Haungpa We arrived at Yeabawme on the 17th [May]. It was a fair sized Burmese village and one of the last on the Burmese frontier. [Hazel is incorrect here: but on the River they would have quite recently crossed from the Burmese area of Kachin into that of Sagaing]. At Yeabawme we met the Forest Officer Rickets and a party of 100 strong. [According to my father, a forester named Ricketts saved the day with his team by blazing a trail through the dense forests from Yebawmi to Hta Man Thi. I have identified in the records a Thomas Charles Donald Ricketts who in 1939, aged 43, was the Deputy Conservator in the Yaw Division of the Burma Forest Service. On 7 July 1942 a T.C.D. Ricketts trekked out to Imphal, India.

Published by the Anglo-Burmese Library 2014. All rights reserved.

|

|

The Burmese Trek WWII

Hazel’s reference to ‘a party of 100 strong’ is corroborated by Professor Pearn’s Report p.115 (Anglo-Burmese Library) where he states that a party of 92 came on elephants by the more direct route from the Hopin railway station to Lonton, on the Indawgyi Lake, .... reached Yebawmi where the party was joined by 17 other evacuees, who had come down the Uyu from Pakhrenbum at the entrance to the Hukawng Valley.] Yeabawme On the 19th [May] evening we camped on the bank of a stream. The carriers built us a shelter of palm leaves. That night about 1 o’clock in the morning we heard a barking deer release a series of terrified barks and immediately after this a tiger roaring. The carriers stirred up the camp fire into a roaring blaze and with flaming torches ran around the camp shouting ‘Cha Cha’ - Tiger, Tiger. But the tiger did not make an appearance, fortunately, and we were left in peace to quell our fears. Next day the 20th we had heavy rain in the afternoon, which did anything but improve the going. We stopped that afternoon to cook lunch at a deserted camp that had been used by preceding parties. That night we slept at another deserted camp. The stream was a distance from this camp. At this camp ‘Malaria’ first made its appearance amongst us. The next day we left this camp 21st [May], some members of the party feeling anything but bright. That evening we reached the bank of the chaung – what a chaung. A mere trickle of water ankle deep and not even a foot wide. This was the source of a swift, wide river that eventually entered the Chindwin. Unimaginable, but true!! The banks on either side of this rivulet were of white sand and pebbles – a great relief to our tired eyes which had taken in nothing but black soggy mud and slush and slime for the last few days. On the 22nd [May] we started walking through this chaung. The pathway which we had been following since Yeabawmi had ended on this chaung. Now we were left with no alternative than to wade through this stream. At first it was only angle deep and the water crystal clear, but gradually it grew deeper and the water black. The bed of the stream was sandy and firm and rocks and pebbles were strewn liberally over its bottom. Various species of fish swam lazily about, causing the undisturbed calm surface of the stream to break into a thousand gentle ripples. The flat, sandy banks rapidly changed into high, overhanging precipices.

Published by the Anglo-Burmese Library 2014. All rights reserved.

|

|

The Burmese Trek WWII

These cliffs rose steeply straight up from the water, their faces smooth and slippery, with blunt and sharp-edged ledges. We came upon the footprints and trademarks of a herd of wild elephants that had been down to the stream to drink in the early hours of the morning. On the top of these cliffs grew wild banana trees. Occasionally, when the cliffs receded from the water’s edge and parts of the actual banks were visible, we were able to walk on land. These occasional strips of land (never more than 50 yards long) were covered with thick tiger grass, growing from 10 to 12 feet high. No regular pathway led through this tiger grass, just a faint trail, recognised by trampled grass. Perhaps no-one imagined what unknown terrors and dangers lurked further inland, if by some mischance one happened to stray from this faint trail. In some places where the depth of the stream was unknown, and impossible to ford, a way had to be cut (or worn away by constant use) along the cliff face itself. A sort of rocky ledge leading up from the water, over the deep pool, and descending to the shallow waters beyond. These ledges were slippery and precarious, and meant sure death if you lost your hold. We camped on the bank that evening having to cut away tiger grass. The stream had deepened and widened considerably. On the 23rd [May] we continued walking through this stream. The scenery did not vary very much, except that the banks were no longer steep, and the surrounding land more open. As we proceeded the granite walls grew less lofty and presently melted away. Water lilies, reeds, rushes and other water plants were in full bloom and we had the unusual advantage of seeing some of the most rare and gorgeous butterflies, insects and dragonflies. We camped on raised ground that evening. The stream at this particular spot was deep black and stagnant with the undergrowth overhanging and growing under the water. At this camp the carriers built rafts as the stream was now deep enough for this primitive means of transport. On the 24th we continued our journey down to the mouth of this chaung, our luggage travelling by raft. The chaung was wide, deep and rapid by now, and we found it more difficult to wade. The banks were now low and grassy, jutting out here and there into the stream. That evening we camped on the bank of the stream, where it widened extensively, no longer a stream now, but a madly rushing, tumbling river – eager to complete its journey from the heights to the plains. Canoes from across the Chindwin, which we had sent for, met us at this point. That day the 25th [May] we travelled several miles downstream and then towards evening the Chindwin was sighted!! Such a gloriously splendid and welcome sight, after days and days of exhaustive endurance and mental agony, combined with the horrors of starvation and the unknown terrors of the primitive wild jungle life. We crossed the Chindwin safely that evening. At the mouth of the chaung where we entered the Chindwin, the river was extensively wide and the current swift and treacherous. The canoes had to be lashed together to make the crossing safely. We slept that night in a village on the west bank of the Chindwin. The wooden hut we slept in actually was a deserted hpongyi-kyaung [Buddhist monastery]. On the 26th [May] we left this village by boat, travelling up stream to Tamanthi. We reached Tamanthi that evening. The Chindwin was very wide now, and we only caught glimpses of the eastern bank. The rocky shores were clothed with bamboo and stunted grass and gnarled tree stumps. Sharp, pointed, black rocks raised their heads above the water, making the Chindwin a dangerous river to navigate. We reached Tamanthi that evening – a pretty little town perched precariously over the Chindwin. With white, brown-roofed bungalows and flower gardens Tamanthi is at the very foot of the lofty ranges – Chin Hills *more correctly ‘Naga Hills’+ which form part of the impenetrable mountain wall of Northern Burma.

Published by the Anglo-Burmese Library 2014. All rights reserved.

|

|

The Burmese Trek WWII

Tamanthi Next morning the 30th [May] we left the dhak bungalow. For the first few miles the going was surprisingly easy, the ground flat and even. Extensive grassy fields bordered the trail. After that the trail wound upwards and downwards past shallow green valleys and ravines. For water, our chief necessity, we depended entirely on our own resources i.e. we could only get water when our tired legs carried us to a stream or spring. Very frequently these streams were situated about 5 or 6 miles apart and what endless misery and thirst-ridden hours we spent in reaching these streams. The problem of water between Tamanthi and Layshi was very acute. That night Mum, Dad and I were separated from the rest of the party and slept alone at the side of the trail. On the 31st [May] as the first streaks of dawn appeared in the Eastern sky, we set forth again – dispirited but game. The trail wound ceaselessly upwards through misty, fresh green jungle. After 3 miles we met some returning Chins [or Nagas?] who, after much persuasion, condescended to guide us to the next camp and also rigged up a litter to carry Mummy. Since the previous day noon we had had nothing to eat, so we did justice to the meal one Chin very kindly shared with us. We reached the next camp after walking about 2.5 miles. Here we met the rest of the party and rested for 2 hours. Refreshing ourselves with pumpkin soup and country spirits, we continued the journey to a dhak bungalow which we reached in less than two hours. We rested here till about 4.30 that evening. While we were here the Chins brought us white pumpkin to eat and more of their country liquor. The dhak bungalow was built on an incline and at the base of the slope was a fair sized stream, and beyond that the trail wound tortuously upwards. We walked till 8 o’clock that night and when we camped it was absolutely dark. I do not know what scenery we passed, but since the pathway led continuously skywards, except when it occasionally descended for short distances, I know that we were approaching the towering height of the Chin [Naga?] Hills. The country was rough and rocky, and the jungle fresh and green, we were leaving the dark, wet tropical forests behind and below us, ascending to the pine, fir and spruce forests. Hazel’s diary finishes here, but she also has the following notes in her Scribbling Book in which she finishes the journey.

Published by the Anglo-Burmese Library 2014. All rights reserved.

|

|

The Burmese Trek WWII

Where I stopped writing(?) Village (Lucklug?) Layshi Village (Cheero’s? Hut) - 3 days – Bridge to be repaired. Kuki village – open (arrived in the afternoon) Parnsat – 3 days B. Camp (crossed Burma/India border) (rain forests to dank tropical forests). Khangung – 3 days (pys?). C. Camp (Chillies & other veg) Phekrokejima (3 or 4 days (Hospital) Camp 1. Dhak bungalow Camp 2. Military (Dhak bungalow) Chips healthy bread Camp 3. Huts Camp 4. Dhak bungalow Kohima 25 June Dimapur railway terminus 26 June

[The Evacuees: Joseph Croft aged 60 Patrick Mark Croft aged 58 Mabel Monin (née Croft) aged 53 Hector Norman Monin aged 58 Douglas Contantine Monin aged 25 Fantrum Jocelyn Monin (née Smith) aged 21 Hazel Joan Monin aged 16 Plus carriers.]

Published by the Anglo-Burmese Library 2014. All rights reserved.

|