Memoirs of

Mrs May Morton

wife of John Morton, Manager, Irrawaddy Flotilla Company

Mrs May Morton

wife of John Morton, Manager, Irrawaddy Flotilla Company

Foreword

|

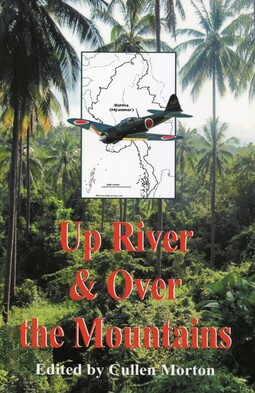

In 1939 the world once again was wracked by war. Europe collapsed as the Axis Powers swept across the continent. Britain remained a bulwark against the spread of nationalist and fascist ideologies. In the Far East, tensions had risen as Japan invaded China. With the subsequent attacks on Pearl Harbour and Singapore in 1941, British possessions in the Pacific came under direct threat. John Morton, a manager with the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company based in Rangoon, was called upon to organize the evacuation of material and personnel as the Army ordered withdrawal up Burma’s river system to establish a northern line blocking the Japanese invasion forces. His wife, May, worked tirelessly in support of the war effort for the Burma War Comforts Association and the Women’s Civil Defence Committee. Each had to make their own way to India. May travelled to northern Burma before flying to Calcutta, while John shepherded the fleet further and further upriver before eventually hiking over razor-back mountain ridges to Manipur. This is their story, in their own words, based on family documents and their personal journals from those troubled days. |

|

Letter from Lillie McClymont, May’s sister

1 February 1976 “. . . when we first knew John Morton, he was home on leave from Burma. He had a father but no mother, two brothers but no sisters. One brother was in England and the younger one just married. His father, George Dickson Morton, was the son of Hugh Morton, a provision merchant in Tradeston. “For many years a Member (Moderate) of Glasgow Town Council George became a Magistrate (Baillie) and, for some years prior to his death, was Treasurer of the Corporation of the City of Glasgow. He worked at William Stevenson & Co. (paint contractors), eventually becoming a senior partner. He was twice married and had three sons by Joanna Longmore and two sons by Alison Lillian Proudfoot. |

|

“George’s second son, John, was a shipping man who went to Burma and ultimately became Manager of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. Ltd. He was married to Mary (May) Elizabeth McClymont in Rangoon and they had four children: Elizabeth, John Dickson, Hamish & Andrew Kenneth. Only two survived their childhood – John Dickson (Jock) and Andrew Kenneth (Ken).

“When Baillie Morton married for the second time in 1920 May attended the wedding, before she sailed for Rangoon to marry Johnnie (as we called him then). George was an exceedingly nice, kind man and, I may say, was strictly “TT” and a non-smoker. We used to go to parties he and Alison gave – the old-fashioned type of party where there was playing, singing, reciting & parlour games – followed by a fine hot supper – great fun. We, the McClymonts, were always very friendly with the Mortons and they came to our parties too! |

|

“Mary Elizabeth Morton was the younger daughter of Andrew McClymont and Elizabeth Haddon Ford McHardy. Andrew was a son of Andrew McClymont, Master Tailor, Mauchline, Ayrshire and Margaret McGregor Colquhoun, but although he learned all about the trade, he was not himself a Tailor. In due course, he and his brother, James, with one other, became partners in a firm of uniform clothing contractors (McClymont, Dewar & Co. Ltd.), making uniforms for Navy, Army, Police, Fire Brigades, etc. (They even at one time fitted out Canadian Units including Band uniform, kilts, sporrans, etc.). Andrew & Elizabeth McHardy were married in 1886, he being 28 years of age and she 21 years. They had 3 children – Andrew, Lillie, and Mary Elizabeth. |

Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, Ltd.

|

John Morton joined the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company and travelled out to Burma in 1912 at the age of 23. He would work for the company until his death in 1942, rising to the position of Manager.

As Dorothy Laird wrote in her history of IFC’s parent company (Paddy Henderson, The Story of P. Henderson & Co., George Outram & Company Ltd, 1961) . . . “The Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, which was to become one of the largest inland waterway companies in the world, had a modest beginning. Few countries are so dependent on water transport as Burma, with its great water system of the Irrawaddy and Chindwin Rivers, as well as the Sittang and Salween.” “The Second World War brought tragedy on a catastrophic scale to the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company. Not only was its magnificent fleet, the greatest inland waterways fleet in the East, almost completely wiped out, but it was destroyed at the hands of its faithful servants, the staff of the Company, in order to prevent the vessels from falling into the hands of the Japanese.” “On January 1, 1942, when Burma was threatened by the Japanese, the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company fleet consisted of 650 fine vessels ranging in type from 325-foot-long paddlers to 50 foot buoying vessels. Four months later, by the end of April, no fewer than 550 of these vessels had been scuttled.” “The wound was the deeper, because the invasion of Lower Burma took place in February, the best month in the year for attempting a sea crossing to India. But at that time the Army was confident that they would be able to hold Upper Burma at least, and the fleet . . . was ordered upriver to act as troop transports, store vessels and hospital ships. By the time the fall of Burma was seen to be inevitable, only four vessels were in a position to take advantage of the sea escape to India.” After war with Japan ended, the IFC returned to Burma as Agent of the Governor for the operation of such Inland Water Transport & ancillary services as necessary to help rebuild the country. Political developments resulted in Burma obtaining independence January 4, 1948 and the company was subsequently nationalized on June 1, 1948. The company went into liquidation on June 26, 1950 and was finally wound up on April 18, 1957. In order that China could be supplied during its war with the invading Japanese, construction of a road from Burma to Yunnan Province was started in 1938. John was despatched by the Company to evaluate the road’s condition and potential in the winter of 1939. |

John Morton

Report on the New Road to China

Report on the New Road to China

29th January

Set out from Rangoon by the afternoon train for Mandalay, arriving there at 5.45a.m., met by MacDonald. Found the bus which I am borrowing from Messrs. Steel Bros. and proceeded to fill up with petrol. The tank on the roof holds 10 gallons but there is no way of getting it out the tank unless one tips up the bus or siphons it out. The latter sounds easy, but a rubber tube is necessary. I thought I might buy a piece in Maymyo and after several shops I located a piece belonging to a douche can at the Chemists.

The trip up from Mandalay was uneventful and I soon got into the way of handling the bus.

After a breakfast and strawberries & cream at Maymyo, over which I did not waste much time, I was on the road again.

Found it slow going on account of the Military moving out to camp and they cluttered up the road with bullock carts, mule carts, bicycles, horses and of course the infantry.

The bridge over the Goteik Stream is a temporary one and is no doubt stronger than it looks. In any case I made Mg Kan walk over it in case anything happened to the bus.

The road after Hsipaw bifurcates and unfortunately, I took the right hand and the better-looking road. I discovered I had made a mistake after going 20 miles along it. This meant 20 miles back, altogether 40 miles, to get on to the Lashio Road again and I arrived at Lashio at 5.30p.m. Tired but quite pleased to have arrived.

After a bath I went to meet Liu who came up by train along with the cook.

Have decided that as the bus is bigger than I imagined we do not need a second bus. This will be a considerable saving. Made enquiry about a decent driver. Dinner of sausages, eggs & coffee and then to bed.

Set out from Rangoon by the afternoon train for Mandalay, arriving there at 5.45a.m., met by MacDonald. Found the bus which I am borrowing from Messrs. Steel Bros. and proceeded to fill up with petrol. The tank on the roof holds 10 gallons but there is no way of getting it out the tank unless one tips up the bus or siphons it out. The latter sounds easy, but a rubber tube is necessary. I thought I might buy a piece in Maymyo and after several shops I located a piece belonging to a douche can at the Chemists.

The trip up from Mandalay was uneventful and I soon got into the way of handling the bus.

After a breakfast and strawberries & cream at Maymyo, over which I did not waste much time, I was on the road again.

Found it slow going on account of the Military moving out to camp and they cluttered up the road with bullock carts, mule carts, bicycles, horses and of course the infantry.

The bridge over the Goteik Stream is a temporary one and is no doubt stronger than it looks. In any case I made Mg Kan walk over it in case anything happened to the bus.

The road after Hsipaw bifurcates and unfortunately, I took the right hand and the better-looking road. I discovered I had made a mistake after going 20 miles along it. This meant 20 miles back, altogether 40 miles, to get on to the Lashio Road again and I arrived at Lashio at 5.30p.m. Tired but quite pleased to have arrived.

After a bath I went to meet Liu who came up by train along with the cook.

Have decided that as the bus is bigger than I imagined we do not need a second bus. This will be a considerable saving. Made enquiry about a decent driver. Dinner of sausages, eggs & coffee and then to bed.

31st January

Up at seven and glad to have hot tea.

Presented the first of our letters of introduction. Mr. Yao made us very welcome and asked us to lunch - Chinese food, but the nearest to English I have come across. He tells me that he is building a workshop and will have 400 cars stationed here to take the munitions right into China. He expects things to be moving soon but cannot give a date. The railway people say that shipments will start on 7th February. Had a look at the dumps for the shells - corrugated roofs, sandbags and earth. The railway has made a good job of the sidings at a cost of over 1 Lahk. Mr. Yao says the I.F.C. will get a portion of the traffic but that Lashio will be the main route.

I met Mr. Lee who is going to be stationed in Bhamo to superintend shipments made from that end. All complained of dear freights and hadn’t heard of the latest reductions.

Up at seven and glad to have hot tea.

Presented the first of our letters of introduction. Mr. Yao made us very welcome and asked us to lunch - Chinese food, but the nearest to English I have come across. He tells me that he is building a workshop and will have 400 cars stationed here to take the munitions right into China. He expects things to be moving soon but cannot give a date. The railway people say that shipments will start on 7th February. Had a look at the dumps for the shells - corrugated roofs, sandbags and earth. The railway has made a good job of the sidings at a cost of over 1 Lahk. Mr. Yao says the I.F.C. will get a portion of the traffic but that Lashio will be the main route.

I met Mr. Lee who is going to be stationed in Bhamo to superintend shipments made from that end. All complained of dear freights and hadn’t heard of the latest reductions.

Called on Crow, the Asst. Superintendent, and got a pass for the use of the road.

Mr. Yao has given us letters of introduction to the Sawbwa of Mongshi and to officials along the road so as to make the journey fast and pleasant.

Mentioned that Mr. Lockley never called on his way back to tell him of his adventures and conclusions.

Have filled up the car with petrol & oil and have 40 spare tins of petrol on board. There is not a great deal of room for other things, but we shall manage.

The servants are feeling the cold and it is just going to be too bad for them when we climb up higher.

Mr. Yao has given us letters of introduction to the Sawbwa of Mongshi and to officials along the road so as to make the journey fast and pleasant.

Mentioned that Mr. Lockley never called on his way back to tell him of his adventures and conclusions.

Have filled up the car with petrol & oil and have 40 spare tins of petrol on board. There is not a great deal of room for other things, but we shall manage.

The servants are feeling the cold and it is just going to be too bad for them when we climb up higher.

1st February

Ready to start at 6.30 but Mg Hlaing the driver, to whom I had given Rs.20/- advance, did not run up till 7.30 by which time I had sent scouts out to find him.

I drove to start with and found the road very bad. All along it men are working and every few yards there is a heap of metal encroaching on the road and making it anything but easy to drive.

I handed over to Mg Hlaing outside Hose where we had a picnic lunch under a tree. A tin of petrol costs Rs. 5/12 at Hose.

We crossed the border and met the Sawbwa of Gafang at Wanting, then on over pretty bad roads till we came across a huge tree lying right across the road. Along came Mr. Haiow a road engineer in a truck and he tried a diversion. It was not too successful as it took him two hours to go 100 yards. The coolies are Shans who are very inefficient workers. Our car got through at the first attempt but by this time it was dark, and we still had 20 miles to go over very difficult country. However, we arrived at Mengshi about 9 p.m. armed with letters to the Sawbwa. There are 4 Sawbwas here – all brothers and our letters are to the No. 4. He was asleep but later granted us permission to sleep in one of his houses. We were all so tired and cold that we could have slept under the car. We had kippers & beer for dinner and off to bed. The bedroom where we slept had a coat hanger on the wall. I noticed it in the morning. Three truck loads of Chinese workers for the Aerospace Factory passed us. One American in the party.

The Sweli River was in sight for a good part of the day.

Ready to start at 6.30 but Mg Hlaing the driver, to whom I had given Rs.20/- advance, did not run up till 7.30 by which time I had sent scouts out to find him.

I drove to start with and found the road very bad. All along it men are working and every few yards there is a heap of metal encroaching on the road and making it anything but easy to drive.

I handed over to Mg Hlaing outside Hose where we had a picnic lunch under a tree. A tin of petrol costs Rs. 5/12 at Hose.

We crossed the border and met the Sawbwa of Gafang at Wanting, then on over pretty bad roads till we came across a huge tree lying right across the road. Along came Mr. Haiow a road engineer in a truck and he tried a diversion. It was not too successful as it took him two hours to go 100 yards. The coolies are Shans who are very inefficient workers. Our car got through at the first attempt but by this time it was dark, and we still had 20 miles to go over very difficult country. However, we arrived at Mengshi about 9 p.m. armed with letters to the Sawbwa. There are 4 Sawbwas here – all brothers and our letters are to the No. 4. He was asleep but later granted us permission to sleep in one of his houses. We were all so tired and cold that we could have slept under the car. We had kippers & beer for dinner and off to bed. The bedroom where we slept had a coat hanger on the wall. I noticed it in the morning. Three truck loads of Chinese workers for the Aerospace Factory passed us. One American in the party.

The Sweli River was in sight for a good part of the day.

2nd February

Tea & eggs and shaving water at 7.30 but as usual it is impossible to get started at the hour arranged. We got off at 8.50 over a bad road to Lungling. Part of the road is made of river pebbles as big as my head which makes pretty rough going.

The Customs stopped us here and I had to pay Rs. 412/8 duty on the car, which is recoverable on the return.

We called on the Magistrate who visa-ed my passport and asked us to breakfast. We couldn’t wait however, so pushed on over a small valley to the hills. Most of the journey this day was in low gear. The hills are very steep, and quite frightening in parts. The road is scratched along the sides of the hills, which in some cases are almost precipices. It is narrow in places and only fit for one-way traffic. At others two cars can pass and we met the first 8 trucks of the South West Transportation Co. (SWTCo.) going to Chefang where they would meet Burmese lorries with munitions. One passed so close to us that it took the paint off the car.

Even going down hill it is necessary to keep in gear, and often low gear, as it is so steep and the corners so sharp from full lock to full lock that it would be foolish to rely on the brakes.

We built a fire and warmed up what had been cooked the night before. Then on again, up and up, till at last we saw the Salween. Green water, deep and with no shore, the hills just come down like a V with water at the bottom. We must have run along the Salween Valley for 4 miles before we came to the suspension bridge – guarded by a young fellow with a spear. After showing our passport we were allowed to pass and to start the climb on the other side. It is heart breaking work and we got about 6 miles to the gallon. Paoshan was made about 7 p.m. The light goes early here as the mountains shut it out. From the Salween the road is much better, and it was a pleasure to get on to the flat near Paoshan and to make speed even with the lights on.

We stopped at the S.W.T. Co’s place – sentry on duty with fixed bayonet. We were allowed in and made very welcome. A glass of beer to our hosts and they were very friendly. Liu has gone to have Chinese food and I have dined on sausages and have ordered chota hazri for 6 a.m.

Tea & eggs and shaving water at 7.30 but as usual it is impossible to get started at the hour arranged. We got off at 8.50 over a bad road to Lungling. Part of the road is made of river pebbles as big as my head which makes pretty rough going.

The Customs stopped us here and I had to pay Rs. 412/8 duty on the car, which is recoverable on the return.

We called on the Magistrate who visa-ed my passport and asked us to breakfast. We couldn’t wait however, so pushed on over a small valley to the hills. Most of the journey this day was in low gear. The hills are very steep, and quite frightening in parts. The road is scratched along the sides of the hills, which in some cases are almost precipices. It is narrow in places and only fit for one-way traffic. At others two cars can pass and we met the first 8 trucks of the South West Transportation Co. (SWTCo.) going to Chefang where they would meet Burmese lorries with munitions. One passed so close to us that it took the paint off the car.

Even going down hill it is necessary to keep in gear, and often low gear, as it is so steep and the corners so sharp from full lock to full lock that it would be foolish to rely on the brakes.

We built a fire and warmed up what had been cooked the night before. Then on again, up and up, till at last we saw the Salween. Green water, deep and with no shore, the hills just come down like a V with water at the bottom. We must have run along the Salween Valley for 4 miles before we came to the suspension bridge – guarded by a young fellow with a spear. After showing our passport we were allowed to pass and to start the climb on the other side. It is heart breaking work and we got about 6 miles to the gallon. Paoshan was made about 7 p.m. The light goes early here as the mountains shut it out. From the Salween the road is much better, and it was a pleasure to get on to the flat near Paoshan and to make speed even with the lights on.

We stopped at the S.W.T. Co’s place – sentry on duty with fixed bayonet. We were allowed in and made very welcome. A glass of beer to our hosts and they were very friendly. Liu has gone to have Chinese food and I have dined on sausages and have ordered chota hazri for 6 a.m.

3rd February

Mr. Chow lived up to his name and provided us with a very good chota hazri – fried eggs, bits of ham, rice, beans, duck & soup and I made the chopsticks work.

We left at 7.30 to do 162 miles to Shakwan. This sounds easy, but we did not arrive at Shakwan till 8 p.m. The road goes over mountains and then down to the valley of the Mekong. Along this river for miles, then across the bridge after examination by officials and a sentry with up-to-date rifle and ammunition. Then there is a steady climb for miles, the engine temperature was over 200 degrees and at last we had to stop to let the engine cool. We emptied the radiator and filled it with cold water and went on again. Soon we had to stop for the same reason, and we decided to call the halt lunch time. We were on a small burn – icy cold, but I washed my feet in it seeing that I have not had a bath since Lashio on 31st January – only 3 days ago, but it seems a long time. It is of course cold and no sweaty clothes about one – still, I am looking forward to a bath at Kunming. After lunch the car started fine and we made good progress in low gear and then in gear with the spark switched off to brake us down the hills. On the next occasion we had to stop to cool the engine, we asked how far we had to go to Shakwan and were told over a range of mountains. This was somewhat disheartening but there was nothing for it but to go on. We climbed very high - over 8,700 feet and then down to 5000 and up again. It will be fine to see a road with two sides to it. Here there is one side – a wall – and the other side is half a mile across a chasm. The driver has done well. I drove for a little today, but it was just about the time the engine was fading out, so I didn’t enjoy it. We have had several optical delusions today – not only myself but the driver. Sometimes we thought we were running downhill while the streamlet at the roadside was running towards us. It was only when we were around a bend and looking back that we were convinced that the road sloped the way the water went.

There is a moon and we are glad of it for dark falls early in the hills. We have not passed a car today, but road workers are in evidence every mile. All today there has been about 50% of the coolies with goitre, so the water must have too much lime in it and lack iodine. At last we debouched out of a gorge onto the plain of Shakwan and soon the town appeared. I am disappointed with the Chinese towns so far – not even the walled cities have electric lights, and everyone seems to go to bed at 7 p.m. except the children and dogs. No lights appear in the houses for, of course, there are no glass windows. As I write in this old temple, my window is covered with paper – but this is a swell place and the light will no doubt come in at 6 a.m. The welcome here was not so hot as last night. Two officials without a word to say but puso and sih – no and yes. One looks like a German. We offered them some beer, but they are not drinkers. They had a wire to say we were coming but had not prepared anything for us. Not even the usual cup of tea or hot water. They said they didn’t know if we took Chinese food or not, but they might have taken a chance. It has been a tiring day and I am ready to sleep at 9.30 p.m.

A visit to the honourable hole in the floor, which in other countries would be the W.C., is quite an adventure in the dark. Wind whistles round corners and doors creak and slam behind one. There is much to be said for a bathroom adjoining the bedroom as we have in Rangoon. I’m afraid we are pampered. My eye is sore and inflamed with dust and keeping a too close watch on the khud.

Mr. Chow lived up to his name and provided us with a very good chota hazri – fried eggs, bits of ham, rice, beans, duck & soup and I made the chopsticks work.

We left at 7.30 to do 162 miles to Shakwan. This sounds easy, but we did not arrive at Shakwan till 8 p.m. The road goes over mountains and then down to the valley of the Mekong. Along this river for miles, then across the bridge after examination by officials and a sentry with up-to-date rifle and ammunition. Then there is a steady climb for miles, the engine temperature was over 200 degrees and at last we had to stop to let the engine cool. We emptied the radiator and filled it with cold water and went on again. Soon we had to stop for the same reason, and we decided to call the halt lunch time. We were on a small burn – icy cold, but I washed my feet in it seeing that I have not had a bath since Lashio on 31st January – only 3 days ago, but it seems a long time. It is of course cold and no sweaty clothes about one – still, I am looking forward to a bath at Kunming. After lunch the car started fine and we made good progress in low gear and then in gear with the spark switched off to brake us down the hills. On the next occasion we had to stop to cool the engine, we asked how far we had to go to Shakwan and were told over a range of mountains. This was somewhat disheartening but there was nothing for it but to go on. We climbed very high - over 8,700 feet and then down to 5000 and up again. It will be fine to see a road with two sides to it. Here there is one side – a wall – and the other side is half a mile across a chasm. The driver has done well. I drove for a little today, but it was just about the time the engine was fading out, so I didn’t enjoy it. We have had several optical delusions today – not only myself but the driver. Sometimes we thought we were running downhill while the streamlet at the roadside was running towards us. It was only when we were around a bend and looking back that we were convinced that the road sloped the way the water went.

There is a moon and we are glad of it for dark falls early in the hills. We have not passed a car today, but road workers are in evidence every mile. All today there has been about 50% of the coolies with goitre, so the water must have too much lime in it and lack iodine. At last we debouched out of a gorge onto the plain of Shakwan and soon the town appeared. I am disappointed with the Chinese towns so far – not even the walled cities have electric lights, and everyone seems to go to bed at 7 p.m. except the children and dogs. No lights appear in the houses for, of course, there are no glass windows. As I write in this old temple, my window is covered with paper – but this is a swell place and the light will no doubt come in at 6 a.m. The welcome here was not so hot as last night. Two officials without a word to say but puso and sih – no and yes. One looks like a German. We offered them some beer, but they are not drinkers. They had a wire to say we were coming but had not prepared anything for us. Not even the usual cup of tea or hot water. They said they didn’t know if we took Chinese food or not, but they might have taken a chance. It has been a tiring day and I am ready to sleep at 9.30 p.m.

A visit to the honourable hole in the floor, which in other countries would be the W.C., is quite an adventure in the dark. Wind whistles round corners and doors creak and slam behind one. There is much to be said for a bathroom adjoining the bedroom as we have in Rangoon. I’m afraid we are pampered. My eye is sore and inflamed with dust and keeping a too close watch on the khud.

4th February

The Governor’s Cup Day in Rangoon, so we decided to take it easy at Shakwan. A late rise and then a visit to the village to see the traders. We had a talk with one big merchant who buys tea from the Shan States. This struck us as strange – like coals to Newcastle. Twist and cotton are brought in from Lashio and Bhamo. Very little goes out now that the orpiment mines are confiscated by Government. The President of the local Chamber of Commerce, from whom the mines were taken because he was keeping up the price, told us that the mule traffic via Tengyueh is bound to suffer as government officials have been around canvassing for lorry loads for the return trip to Lashio – munitions in and produce out. Up till now there has been no lorry business, but we saw the first 8 going west and they will quote rates to undercut the mules. This sounds bad for us and so our only chance would seem to be to cut rates in a drastic manner and so try to attract the traffic through Nankham. The steamer freight, however, bears very little weight compared with the mule freight. Hides and some bristles go from here, mostly to Kunming.

I am disappointed in this place, as also Talifoo which we visit 10 miles away, as there seems to be little doing but local produce in a small way. Beans, nuts, shoes, saddlery, eating shops and no big export trade. I met Mr. Allan, a missionary in Tali, but he knew of no exports except the orpiment (mines about two stages south of Shakwan), the hides and bristles. The people look healthy but poor and they get along on very little – no electric lights in Talifoo which was a civilised town before London was thought of. All these places shut down at dark and present a dead appearance. They do not want electric light as they do not get up till daylight.

Sanitary arrangements are primitive, streets are very narrow, and stalls encroach on what little room there is. Donkeys, mules and ponies jostle with the people. Today was Market Day in Tali – this happens twice a month only and I imagine things have altered little since the days of Kublai Khan.

At a narrow turning in Shakwan we had to stop for a Chev. car containing Mr. Morch-Hansen of the Texas Oil Co. who is going to Burma to see conditions along the road.

The Governor’s Cup Day in Rangoon, so we decided to take it easy at Shakwan. A late rise and then a visit to the village to see the traders. We had a talk with one big merchant who buys tea from the Shan States. This struck us as strange – like coals to Newcastle. Twist and cotton are brought in from Lashio and Bhamo. Very little goes out now that the orpiment mines are confiscated by Government. The President of the local Chamber of Commerce, from whom the mines were taken because he was keeping up the price, told us that the mule traffic via Tengyueh is bound to suffer as government officials have been around canvassing for lorry loads for the return trip to Lashio – munitions in and produce out. Up till now there has been no lorry business, but we saw the first 8 going west and they will quote rates to undercut the mules. This sounds bad for us and so our only chance would seem to be to cut rates in a drastic manner and so try to attract the traffic through Nankham. The steamer freight, however, bears very little weight compared with the mule freight. Hides and some bristles go from here, mostly to Kunming.

I am disappointed in this place, as also Talifoo which we visit 10 miles away, as there seems to be little doing but local produce in a small way. Beans, nuts, shoes, saddlery, eating shops and no big export trade. I met Mr. Allan, a missionary in Tali, but he knew of no exports except the orpiment (mines about two stages south of Shakwan), the hides and bristles. The people look healthy but poor and they get along on very little – no electric lights in Talifoo which was a civilised town before London was thought of. All these places shut down at dark and present a dead appearance. They do not want electric light as they do not get up till daylight.

Sanitary arrangements are primitive, streets are very narrow, and stalls encroach on what little room there is. Donkeys, mules and ponies jostle with the people. Today was Market Day in Tali – this happens twice a month only and I imagine things have altered little since the days of Kublai Khan.

At a narrow turning in Shakwan we had to stop for a Chev. car containing Mr. Morch-Hansen of the Texas Oil Co. who is going to Burma to see conditions along the road.

5th February

Shakwan to Kunming 280 miles.

Left at 7 a.m. for Sluyming but got on so well that we decided to go right on to Yunnanfu. This was a mistake, as we got in after dark (7.30) and found all the hotels (English, French, Chinese) and even the hospital full up. We managed to get a room for ourselves with the South West Transportation Co. and very glad to get anything – by this time it was 10 p.m. We then looked for a place to eat and found a very third-rate place where I got a cup of coffee, having had nothing since a roadside picnic at 11.30 a.m.

The road was excellent in some parts and bad in others. Work going on everywhere. We climbed 3 ranges but not so bad as the Salween or Mekong divides. The gun was useless as we did not see anything to shoot on the roadside.

About 200 miles from Yunnanfu we saw the first signs of the Burma Railway. Embankments thrown up and 1 bridge, then we missed it for a hundred miles and came across it again about 30 miles from Yunnanfu – embankments and cuttings – evidently they are making small bits here & there and we saw several lorries marked in Chinese “China & Burma Construction Dept.” What strikes me is that they are building a useful bit of railway, even if Burma is a wash out. The railway will near Shakwan – and touch some towns and trade. This will cut out the employment of thousands of coolies, mules, donkeys etc. of which there is a constant stream.

The chief thing we noticed was huge blocks of salt. Evidently the salt is boiled from brine in huge pans and one coolie can carry half a pan load – one piece - or a donkey carries two quarter pieces. It is very unappetising looking salt, much stamped over with excise marks.

We were turned back twice by policemen because our car had not a Yunnan registration plate, so we have left it in the open near a Police Office and have taken to rickshaws.

Shakwan to Kunming 280 miles.

Left at 7 a.m. for Sluyming but got on so well that we decided to go right on to Yunnanfu. This was a mistake, as we got in after dark (7.30) and found all the hotels (English, French, Chinese) and even the hospital full up. We managed to get a room for ourselves with the South West Transportation Co. and very glad to get anything – by this time it was 10 p.m. We then looked for a place to eat and found a very third-rate place where I got a cup of coffee, having had nothing since a roadside picnic at 11.30 a.m.

The road was excellent in some parts and bad in others. Work going on everywhere. We climbed 3 ranges but not so bad as the Salween or Mekong divides. The gun was useless as we did not see anything to shoot on the roadside.

About 200 miles from Yunnanfu we saw the first signs of the Burma Railway. Embankments thrown up and 1 bridge, then we missed it for a hundred miles and came across it again about 30 miles from Yunnanfu – embankments and cuttings – evidently they are making small bits here & there and we saw several lorries marked in Chinese “China & Burma Construction Dept.” What strikes me is that they are building a useful bit of railway, even if Burma is a wash out. The railway will near Shakwan – and touch some towns and trade. This will cut out the employment of thousands of coolies, mules, donkeys etc. of which there is a constant stream.

The chief thing we noticed was huge blocks of salt. Evidently the salt is boiled from brine in huge pans and one coolie can carry half a pan load – one piece - or a donkey carries two quarter pieces. It is very unappetising looking salt, much stamped over with excise marks.

We were turned back twice by policemen because our car had not a Yunnan registration plate, so we have left it in the open near a Police Office and have taken to rickshaws.

6th February

Our first job this morning, after cleaning and putting on a decent suit, was to search for lodgings. We were lucky in getting two rooms just vacated at the Hotel Du Commerce at 15 per day each, so we went back to our room and brought our things.

The boys are meantime located in the car. They have plenty of money for food etc. but accommodation is difficult, and the hotel people do not want them here. Also, the car may be impounded if it is seen on the streets in daylight.

This is just a big village, quite unlike what I expected. There is electric light and W.Cs. which are a blessing. I had excellent coffee and ham & eggs for breakfast and feel like tackling the minister.

Called in on Mr. Miaow, Director of Commerce, Financial Expert and confidante of the Generalissimo. He thinks the road is bound to affect the Tengyueh trade and the only thing we can do is to offer attractive rates that will divert the traffic through Namkham to Bhamo. He is interested in ores (tin concentrates), Tung oil, tea and orpiment and will be glad if we will quote him rates Bhamo/Rangoon. He thinks that western Yunnan is going to develop. So far, it is the most backward province in China.

Saw Mr. T.L. Soong, Head of the Communications. He says we will get traffic (munitions) to Bhamo if we will get a decent road made to the highway. He knows the Namkham/Muse section will not stand up to heavy traffic. I offered to transport the munitions to Chefang and he thinks this proposition might be worked provided our lorry rate is low. He asked me to get in touch with Mr. C.M. Chen about this quotation. With regard to the railway, he assures me the line to Burma will be laid within 8 years and that the Lashio/Kunlong Ferry section will be built whether the Burma Government know about it at present or not. He says they have lots of material – rails etc. – at Hong Kong, Haiphong etc. and these are likely to be sent to Burma. This seems absurd as far as Haiphong is concerned, as the railway runs right to Yunnanfu. The railway has more than it can handle in the way of traffic and all sorts of things are coming through. Today I saw an aeroplane in parts on trucks just arriving. Aeroplanes are over Yunnanfu all the time.

I tried to book to Chungking but the ‘planes are booked a week ahead – I also tried to fly to Hanoi, but there is no seat available for a week.

I called on Mr. Wong of the Bank of China and asked him to dinner. He was very talkative and, like all the educated Chinese I have met, he was very abstemious.

He started the Bank of China here 3 months ago and is about to open a branch at Shakwan, Paoshan and another place I did not know. His idea is to give cheap credit to farmers, miners or anyone who will produce raw material. This raw material must be exported or converted into exportable goods so as to provide the wherewithal to fight the Japanese. The best brains of China are congregated in Yunnanfu (engineers, professors, commercial men, scientists) all imbued with the one idea – to get strong enough to push the Japanese out – and, if this takes time, to develop a nation in the Western Provinces which will carry on and become a power. Industrialism will go ahead. Machinery has been brought from the sacked eastern towns and factories are springing up. Here they have chemical works, salt works, a cotton factory and another cotton factory is being built.

Everywhere can be seen new buildings cheek by jowl with ancient structures. The new Yunnanfu is about a year old and is being superimposed on the old. There is still more mule traffic here than lorry traffic. Most of the streets are too narrow for lorries. Ancient crafts are carried on alongside ammunition clearing stations. Aeroplanes roar overhead but coolies are the chief transport.

All this confirms the opinion that the Western Provinces are being stimulated with brains and capital, but I gather little hope that Burma will share much in it, or rather that the I.F.Co. will benefit.

11 a.m. Called on H.B.M. Consul W.H.C Davidson who gave us a lot of information.

He confirms that the country is wealthy in minerals, tin and coal and that it will be developed rapidly. He thinks the highway an engineering feat, but that it will be subject to breaches in the rains, and that as a business proposition it is unlikely to pay when the munition traffic is over.

The railway will be built, but while T. Y. Boong says three years (and another year) it is likely to be completed within 5 years.

Met Murray of Imperial Airways surveying the lake for a service – asked him to tiffin tomorrow.

Called on the French Consul for a permit to visit French Indo China. Have applied for a seat in the fast train Michilene and a seat in Saturday’s plane from Hanoi.

H. B. M. Consul showed us the Treaty regarding the right of the Chinese to navigate vessels on the Irrawaddy with ores etc. destined for China or from China, subject to the same conditions and dues as British companies. I understand that Mr. Tseng, the Vice Minister, has agreed that the necessary facilities exist for all the business offering.

Called on Tengyueh traders Hone Sain Chan and Yon Chun Chan, silk shippers and orpiment shippers. Both were rather pessimistic about trade with Burma. Their chief complaint was the exchange and the high duties levied by the Chinese Government.

The orpiment mines have been confiscated by Mr. Miaow, who blames it on the Central Government, but the traders say he is doing it for his own ends.

Our first job this morning, after cleaning and putting on a decent suit, was to search for lodgings. We were lucky in getting two rooms just vacated at the Hotel Du Commerce at 15 per day each, so we went back to our room and brought our things.

The boys are meantime located in the car. They have plenty of money for food etc. but accommodation is difficult, and the hotel people do not want them here. Also, the car may be impounded if it is seen on the streets in daylight.

This is just a big village, quite unlike what I expected. There is electric light and W.Cs. which are a blessing. I had excellent coffee and ham & eggs for breakfast and feel like tackling the minister.

Called in on Mr. Miaow, Director of Commerce, Financial Expert and confidante of the Generalissimo. He thinks the road is bound to affect the Tengyueh trade and the only thing we can do is to offer attractive rates that will divert the traffic through Namkham to Bhamo. He is interested in ores (tin concentrates), Tung oil, tea and orpiment and will be glad if we will quote him rates Bhamo/Rangoon. He thinks that western Yunnan is going to develop. So far, it is the most backward province in China.

Saw Mr. T.L. Soong, Head of the Communications. He says we will get traffic (munitions) to Bhamo if we will get a decent road made to the highway. He knows the Namkham/Muse section will not stand up to heavy traffic. I offered to transport the munitions to Chefang and he thinks this proposition might be worked provided our lorry rate is low. He asked me to get in touch with Mr. C.M. Chen about this quotation. With regard to the railway, he assures me the line to Burma will be laid within 8 years and that the Lashio/Kunlong Ferry section will be built whether the Burma Government know about it at present or not. He says they have lots of material – rails etc. – at Hong Kong, Haiphong etc. and these are likely to be sent to Burma. This seems absurd as far as Haiphong is concerned, as the railway runs right to Yunnanfu. The railway has more than it can handle in the way of traffic and all sorts of things are coming through. Today I saw an aeroplane in parts on trucks just arriving. Aeroplanes are over Yunnanfu all the time.

I tried to book to Chungking but the ‘planes are booked a week ahead – I also tried to fly to Hanoi, but there is no seat available for a week.

I called on Mr. Wong of the Bank of China and asked him to dinner. He was very talkative and, like all the educated Chinese I have met, he was very abstemious.

He started the Bank of China here 3 months ago and is about to open a branch at Shakwan, Paoshan and another place I did not know. His idea is to give cheap credit to farmers, miners or anyone who will produce raw material. This raw material must be exported or converted into exportable goods so as to provide the wherewithal to fight the Japanese. The best brains of China are congregated in Yunnanfu (engineers, professors, commercial men, scientists) all imbued with the one idea – to get strong enough to push the Japanese out – and, if this takes time, to develop a nation in the Western Provinces which will carry on and become a power. Industrialism will go ahead. Machinery has been brought from the sacked eastern towns and factories are springing up. Here they have chemical works, salt works, a cotton factory and another cotton factory is being built.

Everywhere can be seen new buildings cheek by jowl with ancient structures. The new Yunnanfu is about a year old and is being superimposed on the old. There is still more mule traffic here than lorry traffic. Most of the streets are too narrow for lorries. Ancient crafts are carried on alongside ammunition clearing stations. Aeroplanes roar overhead but coolies are the chief transport.

All this confirms the opinion that the Western Provinces are being stimulated with brains and capital, but I gather little hope that Burma will share much in it, or rather that the I.F.Co. will benefit.

11 a.m. Called on H.B.M. Consul W.H.C Davidson who gave us a lot of information.

He confirms that the country is wealthy in minerals, tin and coal and that it will be developed rapidly. He thinks the highway an engineering feat, but that it will be subject to breaches in the rains, and that as a business proposition it is unlikely to pay when the munition traffic is over.

The railway will be built, but while T. Y. Boong says three years (and another year) it is likely to be completed within 5 years.

Met Murray of Imperial Airways surveying the lake for a service – asked him to tiffin tomorrow.

Called on the French Consul for a permit to visit French Indo China. Have applied for a seat in the fast train Michilene and a seat in Saturday’s plane from Hanoi.

H. B. M. Consul showed us the Treaty regarding the right of the Chinese to navigate vessels on the Irrawaddy with ores etc. destined for China or from China, subject to the same conditions and dues as British companies. I understand that Mr. Tseng, the Vice Minister, has agreed that the necessary facilities exist for all the business offering.

Called on Tengyueh traders Hone Sain Chan and Yon Chun Chan, silk shippers and orpiment shippers. Both were rather pessimistic about trade with Burma. Their chief complaint was the exchange and the high duties levied by the Chinese Government.

The orpiment mines have been confiscated by Mr. Miaow, who blames it on the Central Government, but the traders say he is doing it for his own ends.

8th February

Still no reply from Eurasia about a seat on Saturday from Hanoi to Kunming. The travel agency still unable to get me a seat in the Michilene tomorrow. Looks like I must go by slow train to Loikai.

Met Mr. Young of the Chartered Bank and bought his place in the Michilene to Haiphong on 9th.

Called on the Sawbwa of Mengshi and thanked him for allowing me to sleep in one of his houses on the way up.

Still no reply from Eurasia about a seat on Saturday from Hanoi to Kunming. The travel agency still unable to get me a seat in the Michilene tomorrow. Looks like I must go by slow train to Loikai.

Met Mr. Young of the Chartered Bank and bought his place in the Michilene to Haiphong on 9th.

Called on the Sawbwa of Mengshi and thanked him for allowing me to sleep in one of his houses on the way up.

9th February

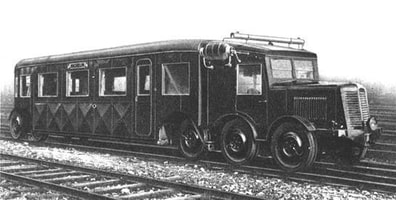

Got a front seat in the Michilene. This is a coach seating 18 first class passengers and about 24 second class. It runs on the rails but has pneumatic rubber tyres. It has a petrol engine not unlike a bus engine and it does the journey down to Loikai in 12 hours against the train – 2 days.

Got a front seat in the Michilene. This is a coach seating 18 first class passengers and about 24 second class. It runs on the rails but has pneumatic rubber tyres. It has a petrol engine not unlike a bus engine and it does the journey down to Loikai in 12 hours against the train – 2 days.

At Loikai there is the French Customs inspection and a very thorough one, especially for the Chinese, whose pockets are felt and emptied if there is much in them. My cheroots were fortunately overlooked. The railway is an engineering feat. The line follows closely rivers for most of the way, at one watershed the height is 8,100 feet. At one stretch you look across a gorge to the railway track on the other side and I’m sure we must have gone through 100 tunnels in 10 miles. Some of the gradients are very steep and some of the descents are made in low gear. Hand brakes are applied suddenly for people on the line or buffaloes crossing. Some of the people pay no regard to whistles or horns and if a party of coolies split up, some wait on one side of the line or road and some on the other. It is certain that just when the train or your car is about to pass, there will be a sudden leap and the minority of the bunch of people rush across to join the majority. This is a most annoying thing to happen when climbing a hill in low gear as you have to stop dead to prevent an accident.

The railway to Hanoi is about 400 miles long and another 70 to Haiphong. It is a metre gauge, single line railway and the French should have had the line doubled on the easy stretches to save time. The capacity of the railway is 8000 tons per month and it is working to capacity. In Tonking the express runs at night but not in China. Bungalows are provided at the night stations for 1st Class passengers, but the lower classes just sleep in the train.

The trains are shut down for holidays. I have met men from all parts of China as this is the only way in. Hanoi is full of people who formerly went through Hong Kong, Shanghai and ports further north. I met the Commander of the “Falcon” which is in the upper Yangtsze and he was proceeding on leave via Chungking, Yunnanfu and Haiphong.

Mr. Finlay Andrew of Butterfield & Swire travelled with me. He was in Kwaiyan when it was bombed the other day and over 900 civilians were killed. The Chinese forced down one of the Jap planes which bombed Yunnanfu.

In the ordinary course of trade, the Hanoi Railway should be able to deal with all the traffic offering - both passengers and goods - but when the whole of Chinese China business has to go this way, it is not up to the work and there are long delays for cargo.

When the war is over, it will again be able to serve the province unless enormous industrial development takes place. Development is in the air. The cotton factory here has 10,000 spindles and another is being built for 25,000 spindles. A certain amount of cotton is grown in the neighbourhood, but raw cotton and yarn are also imported. The cultivation of silkworms is also being started by the Government and mulberry trees being planted.

The natural outlet of silk, Tung oil and other things which come chiefly from Szechuan, the rich neighbouring province, is down the Yangtsze river and I cannot imagine the Japs putting such restrictions on shipping as to force trade to go by other routes. There is a war on, and this does not apply at the moment, but the war will not last for ever and trade will then find its way by natural channels - which will not be via Yunnanfu and the railway, nor via the road and Lashio.

I went to Haiphong to have a look at the docks and saw much congestion. This is the small rains there and lots of cases were stored in the open in the wet. I saw thousands of tons of rails, some marked Hong Kong. I also saw some of Mr. Miaow`s tin ingots awaiting shipment. The quantity of cars, trucks, and lorries was amazing. The French put a restriction on the export of them to China, hence the accumulation. Then they permitted one car per hour to be exported and now they allow 30 per day across the border. As the rail cannot deal with the quantities waiting, the cars are assembled at Haiphong and motored along the road to Longson on the border. From there they find their way inland both to Yunnanfu and further north to Chungking etc. The question of petrol for the enormous number of cars must be a difficult one and the more cars there are, the more petrol will be required, adding still further to the congestion on the railway. All the petrol comes up in 40-gallon drums. There are no tank wagons and no petrol pumps.

Haiphong is a poor place, only important because of the war. I arrived at 9.30 a.m. and had seen all I wanted to see – including 2 sternwheelers for the river – by noon. I had 50 minutes to wait for the Autorail (another petrol car which runs on the ordinary rails) so had a coffee and sandwich and a haircut.

The Anamites are not unlike the Burmese, but they chew cutch and have black teeth in consequence.

Some of the ladies are very smart, good looking and good figures.

I managed to get into the Metropole at Hanoi for the night and wallowed in a hot bath. There was quite a party at dinner. All Andrew`s guests - 3 ladies and 4 men. Murray of Imperial Airways, Far Eastern Manager, was there. We had quite a good night.

The railway to Hanoi is about 400 miles long and another 70 to Haiphong. It is a metre gauge, single line railway and the French should have had the line doubled on the easy stretches to save time. The capacity of the railway is 8000 tons per month and it is working to capacity. In Tonking the express runs at night but not in China. Bungalows are provided at the night stations for 1st Class passengers, but the lower classes just sleep in the train.

The trains are shut down for holidays. I have met men from all parts of China as this is the only way in. Hanoi is full of people who formerly went through Hong Kong, Shanghai and ports further north. I met the Commander of the “Falcon” which is in the upper Yangtsze and he was proceeding on leave via Chungking, Yunnanfu and Haiphong.

Mr. Finlay Andrew of Butterfield & Swire travelled with me. He was in Kwaiyan when it was bombed the other day and over 900 civilians were killed. The Chinese forced down one of the Jap planes which bombed Yunnanfu.

In the ordinary course of trade, the Hanoi Railway should be able to deal with all the traffic offering - both passengers and goods - but when the whole of Chinese China business has to go this way, it is not up to the work and there are long delays for cargo.

When the war is over, it will again be able to serve the province unless enormous industrial development takes place. Development is in the air. The cotton factory here has 10,000 spindles and another is being built for 25,000 spindles. A certain amount of cotton is grown in the neighbourhood, but raw cotton and yarn are also imported. The cultivation of silkworms is also being started by the Government and mulberry trees being planted.

The natural outlet of silk, Tung oil and other things which come chiefly from Szechuan, the rich neighbouring province, is down the Yangtsze river and I cannot imagine the Japs putting such restrictions on shipping as to force trade to go by other routes. There is a war on, and this does not apply at the moment, but the war will not last for ever and trade will then find its way by natural channels - which will not be via Yunnanfu and the railway, nor via the road and Lashio.

I went to Haiphong to have a look at the docks and saw much congestion. This is the small rains there and lots of cases were stored in the open in the wet. I saw thousands of tons of rails, some marked Hong Kong. I also saw some of Mr. Miaow`s tin ingots awaiting shipment. The quantity of cars, trucks, and lorries was amazing. The French put a restriction on the export of them to China, hence the accumulation. Then they permitted one car per hour to be exported and now they allow 30 per day across the border. As the rail cannot deal with the quantities waiting, the cars are assembled at Haiphong and motored along the road to Longson on the border. From there they find their way inland both to Yunnanfu and further north to Chungking etc. The question of petrol for the enormous number of cars must be a difficult one and the more cars there are, the more petrol will be required, adding still further to the congestion on the railway. All the petrol comes up in 40-gallon drums. There are no tank wagons and no petrol pumps.

Haiphong is a poor place, only important because of the war. I arrived at 9.30 a.m. and had seen all I wanted to see – including 2 sternwheelers for the river – by noon. I had 50 minutes to wait for the Autorail (another petrol car which runs on the ordinary rails) so had a coffee and sandwich and a haircut.

The Anamites are not unlike the Burmese, but they chew cutch and have black teeth in consequence.

Some of the ladies are very smart, good looking and good figures.

I managed to get into the Metropole at Hanoi for the night and wallowed in a hot bath. There was quite a party at dinner. All Andrew`s guests - 3 ladies and 4 men. Murray of Imperial Airways, Far Eastern Manager, was there. We had quite a good night.

11th February

Rose late and was driven out to the aerodrome. Quite a nice place – Rangoon is a poor effort beside it. The Eurasia plane (3 Junker engines) had 13 of us, but we had a comfortable flight at about 13,000 feet for a bit, but there was a strong wind and he came down to avoid it and got into some bumps. The journey took about 3 hours. The train (Grand Vitesse) takes 3 days. Mr. Wong of the Bank of China was up meeting the Bank`s research officer and drove me to the hotel.

The visit to Haiphong was worthwhile and I know what we are up against now.

The aerodrome at Kunming is closely guarded and everything very secret. Before landing, the steward comes around and pulls down all the blinds so that passengers will not see the aerodrome or the machines on it.

Had an interesting talk with Williamson of B. & S. regarding trade in general. They still have boats plying in the Upper Yangtsze, but they cannot go down river as the Japs have closed it. The coastal trade is also very difficult as the Japanese have obstructive regulations. Japanese steamers are plying for passenger & goods traffic on the Yangtsze, although they are supposed to be carrying only war material.

Rose late and was driven out to the aerodrome. Quite a nice place – Rangoon is a poor effort beside it. The Eurasia plane (3 Junker engines) had 13 of us, but we had a comfortable flight at about 13,000 feet for a bit, but there was a strong wind and he came down to avoid it and got into some bumps. The journey took about 3 hours. The train (Grand Vitesse) takes 3 days. Mr. Wong of the Bank of China was up meeting the Bank`s research officer and drove me to the hotel.

The visit to Haiphong was worthwhile and I know what we are up against now.

The aerodrome at Kunming is closely guarded and everything very secret. Before landing, the steward comes around and pulls down all the blinds so that passengers will not see the aerodrome or the machines on it.

Had an interesting talk with Williamson of B. & S. regarding trade in general. They still have boats plying in the Upper Yangtsze, but they cannot go down river as the Japs have closed it. The coastal trade is also very difficult as the Japanese have obstructive regulations. Japanese steamers are plying for passenger & goods traffic on the Yangtsze, although they are supposed to be carrying only war material.

12th February

Left Kunming at 10 a.m. and quite glad to be on the way home.

The road is quite cut up – potholes over the first 30 miles where there is a considerable traffic in buses. There are good stretches and bad, and cars will not last long on the road.

We arrived at Tsuyaung about 4 p.m. and managed to buy 4 cans of petrol – said to be 5 gallon – but these are American gallons and the can goes into 2 two-gallon tins. Started making the tents and got a soldier to help sew them. Guards on all night with fixed bayonets – bed at 7 p.m. and it was pretty cold.

We saw 16 trucks arrive (South West Transportation Co`s depot), 8 from each way. Those from the capital carried a few drums of petrol but those coming from the direction of Burma were empty, and they told us they were merely trying out the road before carrying loads. It seems an expensive experiment, especially as several lorries (such as ours) have been over the road and reported on it.

Left Kunming at 10 a.m. and quite glad to be on the way home.

The road is quite cut up – potholes over the first 30 miles where there is a considerable traffic in buses. There are good stretches and bad, and cars will not last long on the road.

We arrived at Tsuyaung about 4 p.m. and managed to buy 4 cans of petrol – said to be 5 gallon – but these are American gallons and the can goes into 2 two-gallon tins. Started making the tents and got a soldier to help sew them. Guards on all night with fixed bayonets – bed at 7 p.m. and it was pretty cold.

We saw 16 trucks arrive (South West Transportation Co`s depot), 8 from each way. Those from the capital carried a few drums of petrol but those coming from the direction of Burma were empty, and they told us they were merely trying out the road before carrying loads. It seems an expensive experiment, especially as several lorries (such as ours) have been over the road and reported on it.

13th February (Monday)

Up at 5.30 a.m. Shaved & dressed by 6 a.m. Breakfasted and started before 7 a.m. A cold day, the ground white with frost. Saw a pheasant and was lucky enough to hit it. It flew across a river before falling and Mg Hlaing waded across for it. A fine cock with beautiful plumage.

The road was good for this stretch (to Shakwan) except for the many diversions where pucca bridges are being built to replace the wooden ones.

The hills near Talifoo are topped with snow (not white marble) and the wind is cold.

Arrived Shakwan 3 p.m. and finished work on the tents. Went through the bazaar and met two American missionaries from the Tibet border who were waiting for friends to arrive. They were putting up at the inn.

We were fortunate to have letters to the S.W.T.Co. establishments where we have always managed to get a room to ourselves, sometimes one for each.

These depots are mostly temples with large courtyards where the lorries can turn and lie for the night. We passed the aerodrome at Tsuyaung – empty but the `drome at Yunnanfu had about 100 planes on it. Many were taxying about, but none in the air. Lots of budding aviators being drilled.

Up at 5.30 a.m. Shaved & dressed by 6 a.m. Breakfasted and started before 7 a.m. A cold day, the ground white with frost. Saw a pheasant and was lucky enough to hit it. It flew across a river before falling and Mg Hlaing waded across for it. A fine cock with beautiful plumage.

The road was good for this stretch (to Shakwan) except for the many diversions where pucca bridges are being built to replace the wooden ones.

The hills near Talifoo are topped with snow (not white marble) and the wind is cold.

Arrived Shakwan 3 p.m. and finished work on the tents. Went through the bazaar and met two American missionaries from the Tibet border who were waiting for friends to arrive. They were putting up at the inn.

We were fortunate to have letters to the S.W.T.Co. establishments where we have always managed to get a room to ourselves, sometimes one for each.

These depots are mostly temples with large courtyards where the lorries can turn and lie for the night. We passed the aerodrome at Tsuyaung – empty but the `drome at Yunnanfu had about 100 planes on it. Many were taxying about, but none in the air. Lots of budding aviators being drilled.

14th February

Left Shakwan 7.45 a.m. and, to oblige the Station Officer, agreed to carry one of his men to Paoshan. I think he was a Jonah. He had tried to get to Paoshan several times, but always something happened, and last time the lorry capsized and he got a broken shoulder.

The car was going well till we ran into heavy rain, which made the road very slippy. Going up hill this was not so bad, but when we crossed the range leading down to the Mekong, it was not so easy and at one part with a very steep descent the driver tried to drop into low gear to brake the car. Unfortunately, something happened underneath - I think at the rear universal joint - and there was a groaning noise as if some teeth had been broken and were loose amongst the works. We stopped and tried to open out the coupling rod, but our tools could not turn one or two of the nuts and bolts. We decide to go on for a few miles in free wheel, relying on the brakes. The breakdown happened at noon in the rain, and we ultimately came to a broken-down Fargo bus and a road mender`s hut and decided to stop there for the night, it being now 5.30 p.m. and dark. Fortunately, the driver of the Fargo bus R.C.4887 had left his tools at the road mender`s hut and we were able to borrow them after an argument with the road mender. We must know what is broken before we can send anyone to Lashio or Rangoon for a spare part.

A cup of Horlicks and a tin of sardines for dinner, as the pheasant stew they are making will take too long and we are tired.

This spot between Yungpang and the Mekong is over 7,000 feet high and cold. There is snow on the hills around. Liu and I slept in the broken Fargo and Mg Hlaing in our car. The others got into the hut. It rained during the night and hailstones kept us awake at intervals.

Left Shakwan 7.45 a.m. and, to oblige the Station Officer, agreed to carry one of his men to Paoshan. I think he was a Jonah. He had tried to get to Paoshan several times, but always something happened, and last time the lorry capsized and he got a broken shoulder.

The car was going well till we ran into heavy rain, which made the road very slippy. Going up hill this was not so bad, but when we crossed the range leading down to the Mekong, it was not so easy and at one part with a very steep descent the driver tried to drop into low gear to brake the car. Unfortunately, something happened underneath - I think at the rear universal joint - and there was a groaning noise as if some teeth had been broken and were loose amongst the works. We stopped and tried to open out the coupling rod, but our tools could not turn one or two of the nuts and bolts. We decide to go on for a few miles in free wheel, relying on the brakes. The breakdown happened at noon in the rain, and we ultimately came to a broken-down Fargo bus and a road mender`s hut and decided to stop there for the night, it being now 5.30 p.m. and dark. Fortunately, the driver of the Fargo bus R.C.4887 had left his tools at the road mender`s hut and we were able to borrow them after an argument with the road mender. We must know what is broken before we can send anyone to Lashio or Rangoon for a spare part.

A cup of Horlicks and a tin of sardines for dinner, as the pheasant stew they are making will take too long and we are tired.

This spot between Yungpang and the Mekong is over 7,000 feet high and cold. There is snow on the hills around. Liu and I slept in the broken Fargo and Mg Hlaing in our car. The others got into the hut. It rained during the night and hailstones kept us awake at intervals.

15th February

Got up at 7.30 and wakened Mg Hlaing and set him to work to dismantle the coupling rod. This will take time, and this was the morning we should have been leaving Paoshan with the mules.

We are amongst the pines and - if it were sunny and if there was no trouble – I would be quite happy here for a few days. No car has passed since we had trouble. The road has gone soft with the rain and I don’t think will stand up to a wet season. The boys produced ham & eggs and we are not badly off - except that we can do nothing till we know what is wrong with the car. We are covered with oil and dirt, and some clothes ruined, but have not yet reached the trouble.

Coupling shaft taken out and both universal joints examined and found O.K. Cannot think of anything else, so decide to put back the works and try it.

By this time, it is noon and we have dinner – the best so far – good vegetable soup and chicken stew – hot and well made.

Off we go at 12.30 first very slowly and with the spark off down hill. It is practically down hill all the way to the Mekong. The road is very good, and we are allowed across the bridge without trouble and very little delay. Then the road runs down the river side for about 10 miles. If this drive were in England it would be the most popular. Then a climb up and over the steep range to the Paoshan valley. The engine is pulling well, and we have almost forgotten that it is a crock. Snow on the hills.

We arrive at Paoshan at 5.30 p.m. and are welcomed by Dr. Lin. We have an invitation to dinner by Mr. Wong, the ammunition expert. I contribute a bottle of whiskey, but there is beer from French China, and we are a happy party - except for one serious looking young man who sucks in all his food with a great noise.

Dr. Lin is full of the developments likely to take place in Yunnan in the next few years. Plantations of mulberry for sericulture, chemical works, cotton weaving etc. and he thinks the highway will cause an increase in population along it. He agrees that at present it is not a business proposition owing to the cost of lorries, spares, maintenance, overheads, gas & lube. oil - which work out at a dollar per kilometer or say about 8 annas per mile (6 kilometers to the American gallon).

Got up at 7.30 and wakened Mg Hlaing and set him to work to dismantle the coupling rod. This will take time, and this was the morning we should have been leaving Paoshan with the mules.

We are amongst the pines and - if it were sunny and if there was no trouble – I would be quite happy here for a few days. No car has passed since we had trouble. The road has gone soft with the rain and I don’t think will stand up to a wet season. The boys produced ham & eggs and we are not badly off - except that we can do nothing till we know what is wrong with the car. We are covered with oil and dirt, and some clothes ruined, but have not yet reached the trouble.

Coupling shaft taken out and both universal joints examined and found O.K. Cannot think of anything else, so decide to put back the works and try it.

By this time, it is noon and we have dinner – the best so far – good vegetable soup and chicken stew – hot and well made.

Off we go at 12.30 first very slowly and with the spark off down hill. It is practically down hill all the way to the Mekong. The road is very good, and we are allowed across the bridge without trouble and very little delay. Then the road runs down the river side for about 10 miles. If this drive were in England it would be the most popular. Then a climb up and over the steep range to the Paoshan valley. The engine is pulling well, and we have almost forgotten that it is a crock. Snow on the hills.

We arrive at Paoshan at 5.30 p.m. and are welcomed by Dr. Lin. We have an invitation to dinner by Mr. Wong, the ammunition expert. I contribute a bottle of whiskey, but there is beer from French China, and we are a happy party - except for one serious looking young man who sucks in all his food with a great noise.

Dr. Lin is full of the developments likely to take place in Yunnan in the next few years. Plantations of mulberry for sericulture, chemical works, cotton weaving etc. and he thinks the highway will cause an increase in population along it. He agrees that at present it is not a business proposition owing to the cost of lorries, spares, maintenance, overheads, gas & lube. oil - which work out at a dollar per kilometer or say about 8 annas per mile (6 kilometers to the American gallon).

16th February. (Thursday)

After bother and fash about animals, we at last fixed up with 4 farmers owning 8 animals between them. They did not want to leave home as New Year falls on 18th instant but the Magistrate ordered them to take us to Tengyueh.

No saddles available, no stirrup irons, so a blanket has to do for the saddle straps for a surcingle and bamboo stirrup irons. I prefer to walk, so after saying goodbye to the hospitable Lin, we start off at 10.45 on a 16-mile stage. This road is very steep and old and for many miles is laid with cobblestones. We have a break at 2.30 for half an hour and drink a cup of coffee, then on again till 6 p.m. when we reach the ancient village of Pupiaokai. We are heartily tired, footsore, and my knees feel weak, so we acceded to the muleteers request to sleep in the inn. The mules walk in the front door and through to the back and we find a clean room upstairs overlooking the main street. We are provided with a cup of tea, a basin of hot water and later, a rush light lamp of the Aladdin pattern, not nearly as good as our own lanterns, but just as smelly, all this for about three pence per head.

During the day we met with many caravans, thread from Tengyueh and silk and skins going there. In fact, considering no car passed us while on the road in 24 hours, this route might be called busy.

The first fright our mules got was when our car passed us with Mg Kan and two Chinese workers of the SWT Co. whom Dr. Lin asked us to send to Mongshi. I am only too willing to oblige as he has been very kind to us.

We have a longer march tomorrow, so we went to get to bed as soon as possible. Hla Pe is frying eggs, bacon & tomatoes for dinner and I wish he would hurry up. The eggs cost about 8 annas for 25 - small, but fresh. Liu’s feet are hurting so he has gone out to buy a pair of thin socks – his boots are tight evidently - I don’t know how I am going to get up in the morning. The scenery has been fine – mountains and hills and now this very fertile valley. The pines give place to evergreen, and then lower down, bare hills with coarse grass. The valleys are terraced and all irrigated. We wanted to camp in the woods and use our home-made tents but there are no woods for some miles. It is not so cold here and must only be about 4,000 feet high.

After bother and fash about animals, we at last fixed up with 4 farmers owning 8 animals between them. They did not want to leave home as New Year falls on 18th instant but the Magistrate ordered them to take us to Tengyueh.

No saddles available, no stirrup irons, so a blanket has to do for the saddle straps for a surcingle and bamboo stirrup irons. I prefer to walk, so after saying goodbye to the hospitable Lin, we start off at 10.45 on a 16-mile stage. This road is very steep and old and for many miles is laid with cobblestones. We have a break at 2.30 for half an hour and drink a cup of coffee, then on again till 6 p.m. when we reach the ancient village of Pupiaokai. We are heartily tired, footsore, and my knees feel weak, so we acceded to the muleteers request to sleep in the inn. The mules walk in the front door and through to the back and we find a clean room upstairs overlooking the main street. We are provided with a cup of tea, a basin of hot water and later, a rush light lamp of the Aladdin pattern, not nearly as good as our own lanterns, but just as smelly, all this for about three pence per head.

During the day we met with many caravans, thread from Tengyueh and silk and skins going there. In fact, considering no car passed us while on the road in 24 hours, this route might be called busy.

The first fright our mules got was when our car passed us with Mg Kan and two Chinese workers of the SWT Co. whom Dr. Lin asked us to send to Mongshi. I am only too willing to oblige as he has been very kind to us.

We have a longer march tomorrow, so we went to get to bed as soon as possible. Hla Pe is frying eggs, bacon & tomatoes for dinner and I wish he would hurry up. The eggs cost about 8 annas for 25 - small, but fresh. Liu’s feet are hurting so he has gone out to buy a pair of thin socks – his boots are tight evidently - I don’t know how I am going to get up in the morning. The scenery has been fine – mountains and hills and now this very fertile valley. The pines give place to evergreen, and then lower down, bare hills with coarse grass. The valleys are terraced and all irrigated. We wanted to camp in the woods and use our home-made tents but there are no woods for some miles. It is not so cold here and must only be about 4,000 feet high.

17th February

Chinese New Year’s Eve. Went to bed at 7 p.m. but there were two weans howling and, tired as I was, I couldn’t get to sleep. There was a Hnyaw – the smell of frying which in Burmese is very bad for the health. The fumes of Chinese tobacco came up through the floor. The hostess was quarrelling with her husband for hours – leastwise I suspect he was her husband as he never said a word. Then I had to get up twice in the night sick. Altogether, the Chinese New Year’s Eve has found me far below par and our longest march, 90 li, tomorrow. I don’t know how far this is, but we marched 6 hours without a halt, then halted for ¾ hour at the Salweeen bridge – then on up hill – very, very steep for another 5 hours. Liu was pushing my back at places and was a help. It was too steep to ride. Tomorrow we do 80 Li and I am having Horlicks for dinner and hope my tummy will be better. It is bad enough to march about 18/19 miles up hill and down dale if one is fit – but if one is feeling below par, it is just too bad. Our muleteers, 4 of them, have no bedding, no pots with them, so have to sleep in an inn. I was mighty glad to see this one and to get my feet into hot water. The most disappointing thing about this route is that if you want to see the scenery you have to stop and look. You may not take your eyes off the path while walking. It is either cobble stone with the emphasis on the cobble or it is made alongside a precipice. We saw fewer caravans today and the road was not so busy. It is a hard road at the best of times and our mules are farm mules, not transport, hence we go slower. They are all galled, and the men do nothing for them. Considering there are 4 men and 8 animals, they should get the best attention. I have my camp cot set up on top of a verminous bed and hope things will be O.K. I am too tired to worry. The white ponies are better looked after than the mules, and they do much less work. It was cloudy when we crossed the Salween and I doubt if my photos will come out. In any case I was too ill to bother about cameras. This route is for fit men only and I hope to be well tomorrow. I am going to bed now at 6.30 p.m. High life in the East. It is high in one respect, as we must be up at 7,000 feet.